Discover more from One Thing

Today we review two art exhibitions to seek out this summer.

Kyle Chayka: There’s a particular NYC-area dating ritual in which, perhaps around the two-month mark when both parties are definitely serious and want to lock it down, the nascent couple takes a trip up to Storm King, a sculpture park in the Hudson Valley. They might hold hands strolling past the monumental Calders and di Suveros. A few dates more and then they have to make an appearance at Dia Beacon, the enormous minimalist art museum conveniently located off Metro North. There they gaze into the blank eternity of Gerhard Richter’s reflective panels. Then they have to get married (at some farm venue in the Catskills). But there’s a new, better addition to this lineup. Magazzino, an austere compound of concrete boxes in Philipstown, NY, presents a collection of latter-twentieth century Italian art. The museum might not catalyze your relationship, but it will at least give you a rare education in contemporary art history.

Jess and I headed to Magazzino after staying a night in Cold Spring, NY, for a friend’s wedding. The museum is just a short drive away from the town, which is absolutely packed with crop top-wearing tourists from Bushwick who took the train instead of a car, and so can’t get very far from downtown. On a weekend, at least, the museum was nicely quiet without feeling like a mausoleum. It is the work of Nancy Olnick and Giorgio Spanu, a collector couple whose hoard of Arte Povera is both enshrined and marketed by their private collection turned public institution. (It bears mentioning that this makes for an excellent tax write off.) It originally opened in 2017, but expanded with a new pavilion in 2023. Arte Povera is something of a niche or an acquired taste — the Freak folk version of modernist sculpture. I personally love it. It’s a bit like if industrial American Minimalism got tossed into a thrift store. The Arte Povera artists didn’t just use clean sheets of metal and glass; they covered them with old clothes, leather shoes, grungy newspapers. It’s a very specifically Italian movement, with plentiful fragments of classical sculpture and Mediterranean kitsch.

Perusing Magazzino is like hearing a great DJ set: all killer no filler, a retrospective of a body of work you didn’t know you were missing out on. Unlike the installations at Dia, the art is fun and chill, with a pronounced sense of humor. Funny art is underrated, especially when it’s also deeply enmeshed with art history. Jannis Kounellis is one of the most internationally famous Arte Povera practitioners. At Magazzino we saw a revelatory wall-mounted Kounellis sculpture of rusted steel girders set with little hanging platforms each piled with improvised pyramids of ground coffee. Such sprezzatura! I didn’t know the work of Giovanni Anselmo but quite liked his pieces, including “Direzione” (1967-78) a big, rough-hewn block of stone embedded with a compass in its top, installed on the floor pointed north. Weighted by mass and magnetism, the sculpture would never move. And there was a powerful untitled piece by Pier Paolo Calzolari from 1989, a sheet of copper the size of an Abstract Expressionist canvas perforated with holes, with an active freezer tube running through it. The copper frosts over with white like the inside of an icebox, creating a looming, live presence in the room that can be felt as well as seen. These are poetic material epiphanies. If your date isn’t into it, break up with them.

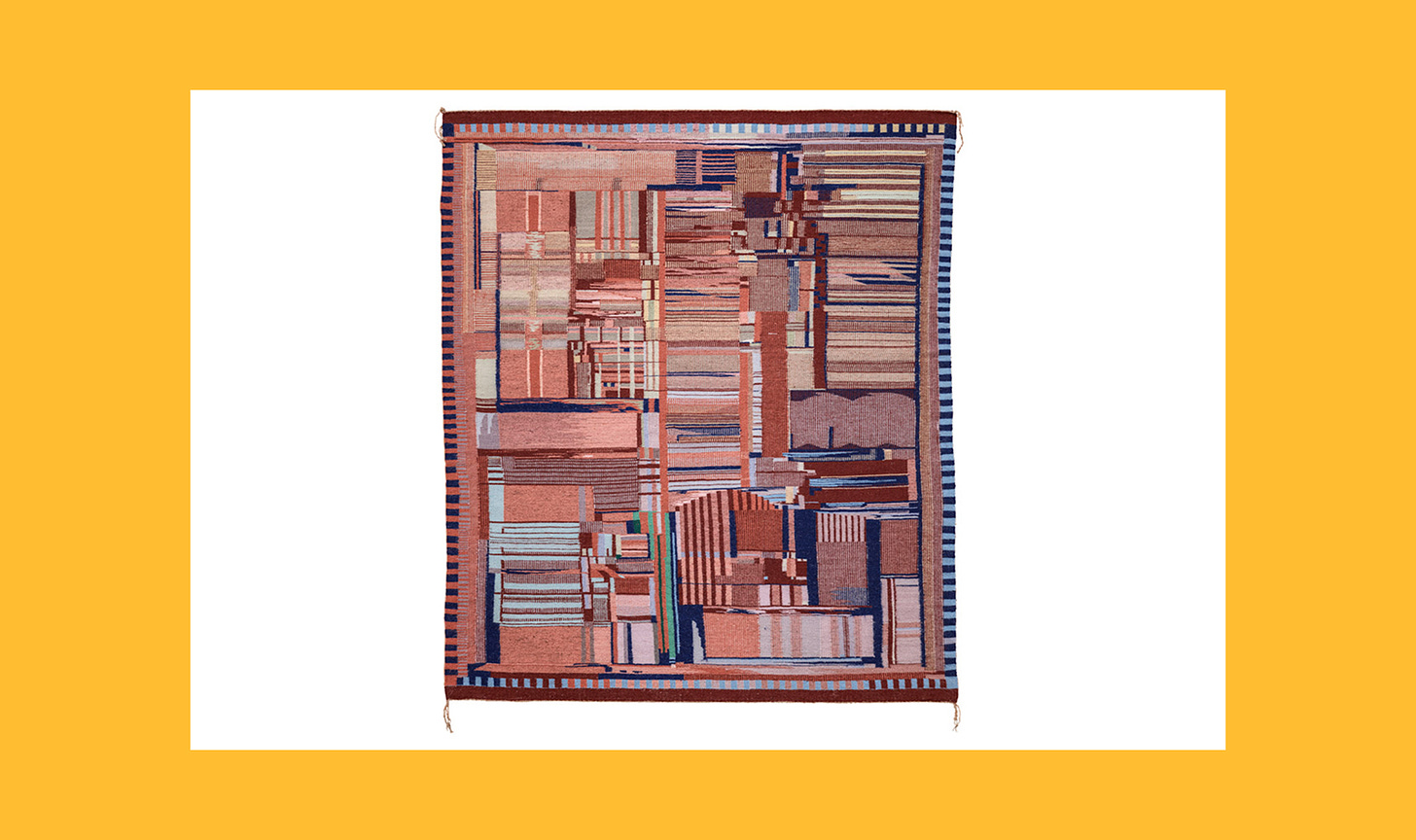

Nate Gallant: Last weekend was searingly hot for most of the eastern seaboard, yet I cannot shake an uncanny feeling of coziness after a visit to the National Gallery’s modern wing. Despite the awful DC humidity, I found myself taken in by the warm invitation of a deeply engaging exhibition of woven art. In this case, less Ken Burns Americana fantasy and more in the key of Native American modernism. The show, Woven Histories: Textiles and Modern Abstraction (running through July 24), placed textile art in various form factors beside more recognizable, painted staples of modern abstract art, highlighting the varying effects of their shared, now quite popular visual vocabulary.

The moment of abstraction that the show highlights is, notably, one of the more popular reference points for our contemporary minimalist aesthetics, which are often commercialized into oblivion. Think shitty Mondrian knockoff shapes in an open concept kitchen, the endless reproduction of subway tiles in commercial space, or just everything in an Apple store. The result is a cheapening proliferation of shiny, flat surfaces, filling our spaces with dull edges and hiding the ghost in the machine of our daily world’s many violently mediated machinations beneath impossibly smooth surfaces. It’s designer technocracy.

I imagine this mire of faux minimalism and DC-area junkspace resulted in my fixation on a large textile microchip by Marilou Schultz, a Navajo weaver currently working in Mesa, Arizona, on display at the National Gallery. The guts of contemporaneity were on full display, standing naked in the attractive asymmetric linearity and texture of organic woven patterns. The patterns are both ugly and beautiful, evoking circuit boards as well as the desert landscape, which are both sites of mangled natural resources on which the US has been rebuilt since the birth of Silicon Valley.

Beyond the clever artistic doubling of Big Tech aesthetics, an engineer friend verified the microchip’s technical accuracy. The Woven History exhibition would be worth a ticket price, but luckily in DC the museums are free. Still, back outside, watching the panelists at the Smithsonian’s Folklife Festival bake in the heat and humidity of an overheating earth, light streaming off the ugliest blue-glass monstrosities in the mid-Atlantic in the distance, the price of admission began to seem quite a bit higher.

Subscribe to One Thing

A catalogue of authenticity

Love this, what a neat show for the national gallery!

All that art is complete, contemptible crap.