Emily Chang: When I first moved to New York, I went through a period of jumping from one apartment to the next. In two years, I lived in five apartments, not because I wanted to, but because of various plights of living in the city: Roommates moving out, random couch-surfers, burglary, the landlord selling the building.

Every time I had to move, packing each item was like a punishment for having bought it. After repeating this task, I started to be more selective with what I bought. Everything had to be exactly what I wanted, or I just didn’t buy it. I liked the idea of being able to pack everything up and move at a moment’s notice, if I wanted to. I started to think a lot about space: Physical space, what we could do with it, how New Yorkers were simultaneously obsessed with having space and also surprisingly tolerant of not having any at all, and how, while we’re paring down our IRL existences to the essentials, we’re doing the opposite in our digital lives.

Physical minimalism is meeting digital maximalism, and nothing is more indicative of the overflow than our phone camera rolls. The camera roll has become a hard drive for our brains, an external device that lives life alongside us, a place for us to store away what we don’t have space for at the forefront of our minds. It also gives us the power to enact memories from the past. Let your finger hover over the grid, pick the moment you want, and drop in. And there’s no question as to which of these moments to store, because the space is essentially unlimited.

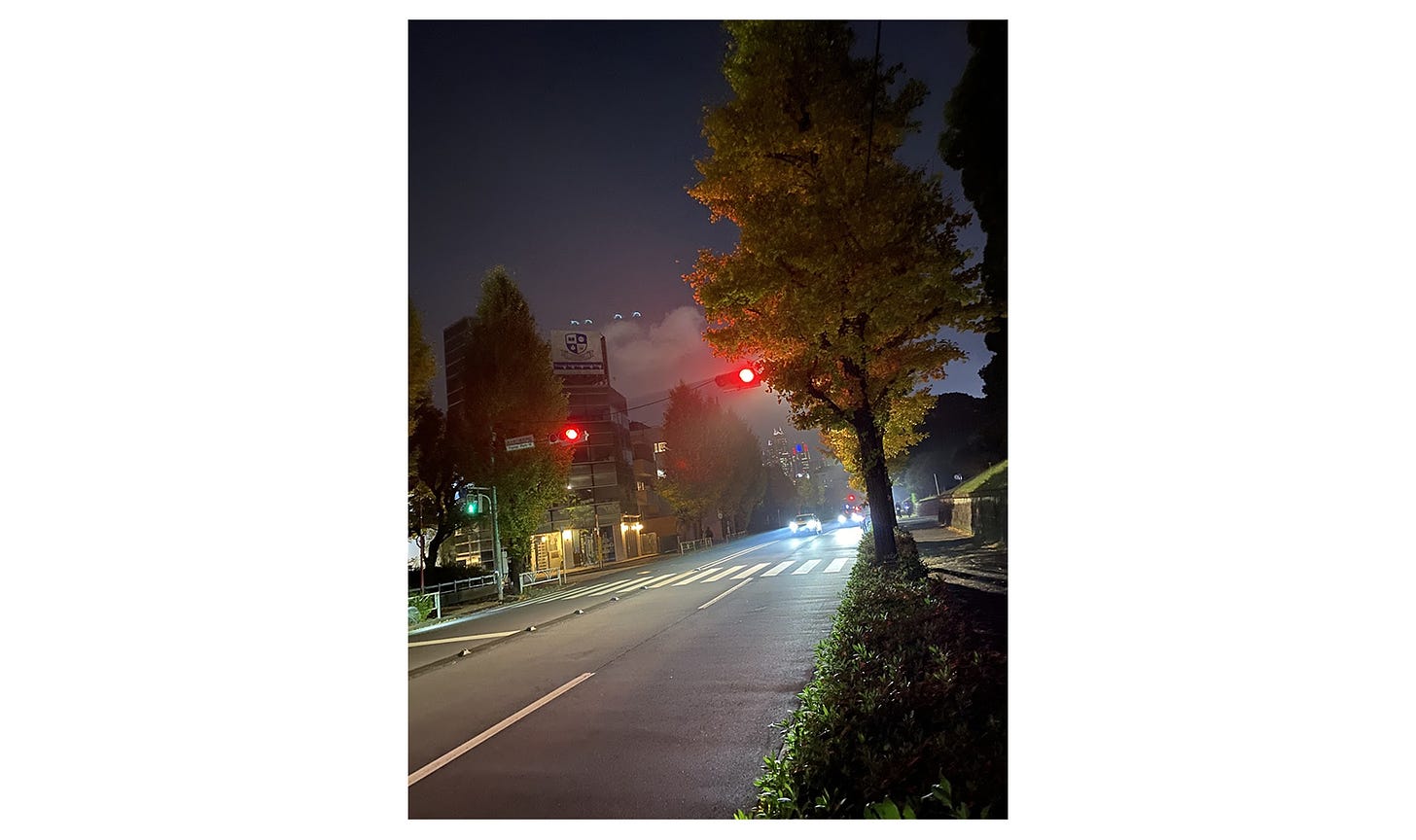

In my camera roll, there’s a picture: Hazy red traffic lights on an empty street bordering Yoyogi Park in Tokyo. A big, bushy, looming tree. Softened colors, a Gaussian blur applied on siren red, the calm midnight blue of the night sky, the white of the fog, the green of the forest.

Like many pictures in my camera roll, it’s unremarkable. And yet, unlike other pictures taken that night, it conjures up for me a potent memory that’s not exactly depicted within the photo, but with a few taps I can always evoke it. I took it when I was in a cab on my way back to my hotel in Shibuya. I was alone in Tokyo and didn’t know a single person, but I had just met a photographer from London at New York Bar at the top of the Park Hyatt, with whom I shared a dozen mutual friends. Not only that, but he had just taken a meeting in my office the previous week. Life suddenly felt loud and significant, my body weighed down with the confidence that my presence had some kind of density on the other side of the world. I was not made of air in Tokyo, a floating free radical in the crowds; I was here.

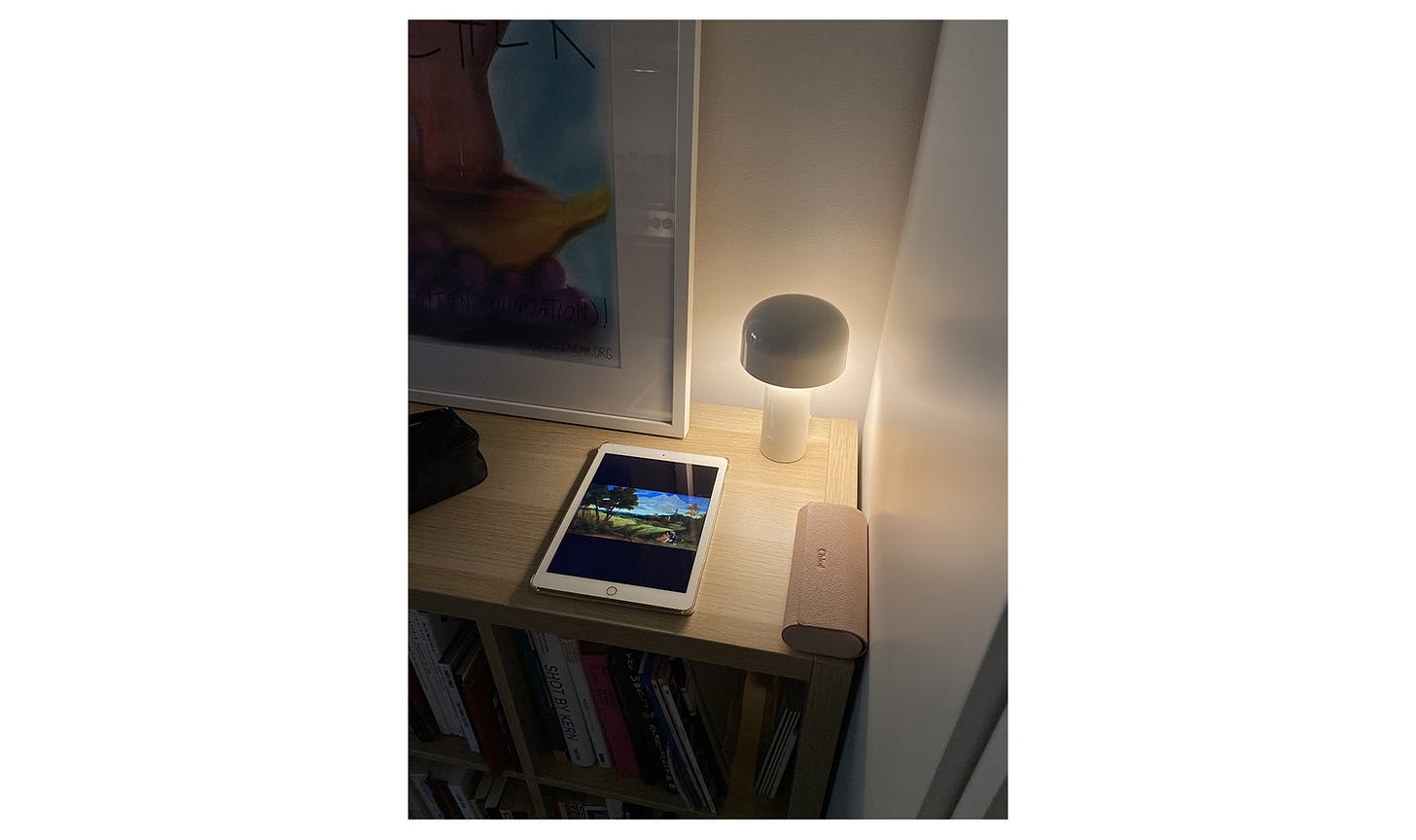

Other photos stir up other vivid memories: An image of my watch, taken as I walked over the Manhattan bridge, evokes the scents and sounds of a particularly formative summer; a dimly lit scene from a birthday party, all pure whites and creams and squiggly details in the shape of a lamp’s neck, the jagged edges of its shade blown up in shadow, warm candles staggered at different heights, encapsulates the memory of an entire season. And yet there is nothing particularly recognizable in the picture. It’d be hard to say what it’s a picture of, exactly, and I don’t even know who the girl in the background is.

Today, not only is the camera roll a collection of visual portals that one can use to access the past; the overflow of imagery also captures everything that’s not in the frame. We can take infinite images, so we take pictures of anything and everything, oftentimes in quick succession, which has become such a problem that Apple even created a feature that tells you how many repeats of an image exist on your phone.

These unexceptional repeats have a surprising value, however. Just as smell, our most nebulous, non-literal sense, has the ability to take an indefinable scent and trigger precise memories, there is something specific about certain images that are so imprecise that they pull from our entire consciousness to organize meaning.

Take another snapshot for example. It’s the corner of a Cassina Soriana couch I was sitting on in a late friend’s apartment, and a bit of rug peeking out from under the couch. The picture looks like it was taken by mistake. But it’s the memory of the texture of that cognac leather, wrapped taut around its tough, oval body that makes me recall a particular exchange, re-ignited every time I look at this image:

“What’s the rarest thing in this apartment?” I asked him.

“Me,” he replied. And he was right.

After he passed, many of his belongings and furniture in that apartment — all rare, valuable finds — were sold at an auction. I remember looking through that catalog, a person’s favorite objects that I’d only ever seen in the context of a home, photographed with shocking pristineness, all for sale.

Perhaps the frequency and general mundanity of our digital photography adds more imagination and mental poetry when compared to the more careful capturing of specific, pictured moments. Through our phones and online presences, our existence quite literally transcends time and space. Ultimately, I’m not sure if that is for better or for worse.

It is a boundary-less existence, a home in your head that never runs out of room in which to store furniture and objects. Memories still fade with time, but now you can see them all again in two seconds if you want to, and not just family trips to the Grand Canyon, college graduations, and your parents’ favorite photos of you as a baby in your old house, but everything, every moment, every day. The ten angles you shot before the right one.

While countless articles and TV shows preach the virtues of minimalism, in tidying our homes and throwing out clothes, and despite “digital cleanses” which never did catch on, we collect and create digital things on a gargantuan scale: screenshots, videos, posts on social media, likes, saves, messages, and interactions. We’re encouraged to pare it down to the most essential physical things in life and encouraged to do the exact opposite in our digital lives. We are all “creators” after all.

Despite society’s obsession with “good” pictures, you don’t need to have a good reason to take or even keep one forever, when you can do it in .0001 seconds and delete it just as fast, when you can have 10TB of iCloud storage, when the limit to how many Instagram Stories you can post a day is a whopping 100, when you can scroll past thousands of images per day on your feed both vertically and horizontally, when images are on every article you read, every ad on every street; when you live in a culture in which image is everything, but hot pics get switched out for new ones at the tap of a button and at the sign-off of multimillion-dollar campaign budgets that roll out every micro-season. In an age of influencers, in which everyday moments are monetized and pictures have payouts, society will never say no to more images.

If image as byproduct and image as bestseller are at two opposite ends of the spectrum, it’s the push and pull between the two, and those moments when they crash into each other, that’s an unspoken driving force behind culture today. Unlike social media, the camera roll is a private collection of images for your eyes only. When you look at all of them together, the reasons as to why you took one, what’s in it, or the question of its quality almost falls away. In the camera roll, the virtue of the image is completely reframed. A picture is no longer held to the rules of being good or bad, powerful or insignificant, evocative or dull. Rather, the photos maintain their own separate life within us, casting a gaze and a pressure of their own. Instead of possessions we have images; instead of memories, we have castoff snapshots.

In a few weeks, I will be packing up my things and moving yet again; this time, out of choice. As I begin this process, I think about how I will fill the new space that stands just across Manhattan, thirty-four floors taller and a little bigger, with more space to fill. To pack each item is to encounter an object with a past, a reason for being, an emotional connection or lack thereof, the question of whether I should keep it, and if so, which box it should go in. Each of my belongings is now a choice again, just as it was when I first acquired it. As I hold a small vase in my hands, I imagine the new apartment, completely devoid of things — a pure space, with physical boundaries and limitations to what it can contain. I realize that I can’t wait to color in its lines and fill it with the expressions of life until it’s vast, like life.

Emily Chang is a writer and creative director based in New York. Currently, she is Associate Creative Director at Uniqlo Global Creative Lab, working on global brand, special projects, and collaborations. Subscribe to her Substack here for upcoming pieces.

Best of One Thing

If you’re a new subscriber, look back through the archives for our greatest hits. We send out short newsletters on taste, authenticity, and recommendation culture every Tuesday and Thursday (plus some extras).

List culture In cultural recommendations and generative AI, lists still dominate the internet and dictate our culture.

What makes a good newsletter? A roundtable with our favorite critics on the best qualities of newsletter publications.

Autumn sweaters Nate and Kyle’s recommendations for fall fashion purchases, from hoodies to waxed baseball caps.

The beautiful mess of Apple TV+ Slow Horses, Foundation, and Shrinking are all arguments in favor of the most underrated streaming service.

The new Storm King Charli XCX may have played the sculpture park but you should go to Magazzino instead for some Italian postmodernism.

Subscribe to One Thing

A catalogue of authenticity

This essay is such a gem. Thank you!

"In an age of influencers, in which everyday moments are monetized and pictures have payouts, society will never say no to more images."

"Unlike social media, the camera roll is a private collection of images for your eyes only."

"Memories still fade with time, but now you can see them all again in two seconds if you want to, and not just family trips to the Grand Canyon, college graduations, and your parents’ favorite photos of you as a baby in your old house, but everything, every moment, every day. The ten angles you shot before the right one."

"“What’s the rarest thing in this apartment?” I asked him. “Me,” he replied. And he was right."

This has inspired me to look back into my own camera roll and reminisce haha. Thank you